This research was done in cooperation with the Family and Community Historical Research Society (FACHRS), with members investigating their particular community of interest in a project called Communities of Dissent. The following write-up provides key findings of Phase 2 of the project where a detailed analysis was undertaken of the rise of Bible Christianity, an offshoot of Wesleyan Methodism. This project builds on Phase 1 of the project that profiled religious worship in the parish. The full Phase 2 report, including references and some discussion of methods, is available from this link.

Introduction

“Monday, 8th. We commenced our meetings at Bratton Chapel, and had a shaking among the dry bones.

Tuesday, 9th. Sinners cried for mercy, two found peace with God, one of them was a woman aged 69 years… Praise the Lord, Alleluia.

Wednesday, 10th. Another person found the same blessing, and rejoiced in the Lord.

Thursday, 11th. Many sinners were in deep distress; three professed to obtain the love of the Saviour.

Friday, 12th. We had a delightful meeting. After the first prayer meeting, sinners began to cry aloud for mercy, and continued nearly all the time of preaching; seven were in deep distress and six were set at liberty, and rejoiced abundantly in the God of their Salvation.”

In 1818, a group of Methodists known as the Bible Christians arrived in the rural parish of Bratton Clovelly, Devon to spread the evangelical message of salvation for all, beginning a nonconformist tradition that still persists in the community. Using record linkage, a study was conducted to identify the religious preferences of parishioners and to investigate those who adopted nonconformist beliefs. Primary focus areas include the founding and growth of the denomination in the parish and socioeconomic characteristics and migration patterns of its adherents. Methodism permeated Bratton Clovelly widely, both in geographic and socioeconomic terms, and the evidence not only sheds light on the rise of the denomination but also indicates that the nonconformists differed from the Church of England adherents in substantive ways.

The parish

The study area is Bratton Clovelly, a parish in the Lifton Hundred of Devon. The parish covers about 8,000 acres and is situated nine miles west of the market town of Okehampton, thirteen miles north of Tavistock and ten miles east of Launceston and the border with Cornwall. The landscape is one of green, rolling meadows, pastures and fields with Dartmoor rising in the east. During the study period of 1841 to 1911, the clay soil, moorlands in the north and rudimentary transport systems allowed few alternatives to the cattle and sheep farming that still feature in the local economy today.

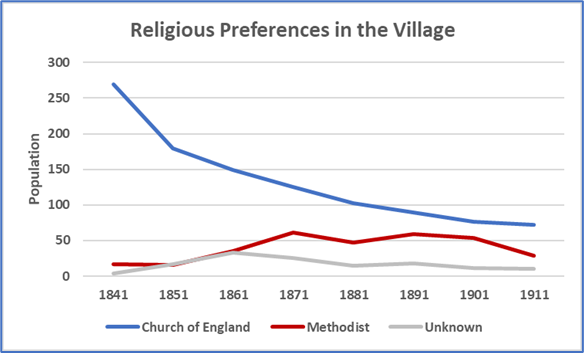

The Bratton Clovelly workforce was almost completely agricultural or those who directly supported the farming activity, with about a fifth of the population resident in Bratton Village. The village was composed of about fifty cottages and buildings to accommodate the school, police station, post office, one to two inns, grocers, tailors, shoemakers, carpenters, smiths and craftsmen, along with some families of agricultural and domestic labourers, the elderly and the poor. The cottages clustered near the ancient St Mary’s parish church whose vicar had a good living with a rectory in the village and about 150 acres of glebe land.

Bratton Clovelly Parish Boundaries, 1851

Bratton Clovelly had a long history of relatively independent farmsteads. It originated from the consolidation of four manors probably in the 12th to 13th centuries and almost all of the fifty or so farms surrounding the village had existed since at least later medieval times, some still carrying names that indicate Anglo-Saxon origins. The earliest manor lords were often non-resident and there was a sizeable number of medieval freeholders. The manor rolls indicate that even leaseholders were conventionary tenants in a predominantly economic relationship with the manor rather than performing services. The pattern of multiple landowners continued and farmsteads provided housing as needed for their labourers, virtually all of whom resided within the parish. Farms were on average 150 acres with a small number over 300 acres and a similar number of smallholdings.

Through most of the study period, the parish was made up of two detached parts stretching for about seven miles from the most northern to southern points. Although re-districting took place in 1885 that transferred the western part of the parish to Broadwoodwidger, the historic boundaries have been used for the full study period. With Bratton Village roughly in the center of such a large parish, a number of farms near the boundaries of the parish were closer to villages in neighbouring parishes than to their own parish village.

The Arrival of Nonconformity

Until the 19th century Bratton Clovelly had been a parish of one religion. In the 18th century, the vicar of the ancient St Mary’s Church reported that ‘We have not any reputed Papists, nor dissenting Congregations’. The living was an attractive one and church leadership remained stable, with learned 19th-century incumbents serving on average 20 years. However, John Wesley’s fast-rising Methodism made change almost inevitable for Bratton Clovelly, with West Devon situated between the Church of England stronghold in the Exeter Diocese to the east and the Wesleyan stronghold in the Cornish mining districts to the west.

A group of Methodist evangelists called the Bible Christians saw a pressing need to spread their message to this part of Devon and North Cornwall. The Bible Christians were founded by William O’Bryan, a Wesleyan preacher from a well-off Cornish family who owned farms and mines. O’Bryan had been drawn to Methodism at an early age and although he twice unsuccessfully applied to be accepted as a minister, he pursued local preaching and provided the land and chapel that still stands at Gunwen, Cornwall. Driven by his ‘imperious duty’ to evangelical outreach, his self-defined preaching plans eventually contributed to his rejection from several Wesleyan Societies for lack of discipline. By that time, he had met the Thornes of Lake Farm in Shebbear about ten miles north of Bratton Clovelly and together they formed the first Bible Christian Society in 1815. Lake Chapel opened in 1817, Shebbear became the focal point for the denomination and leadership of the Bible Christians would eventually pass from William O’Bryan to James Thorne.

Initially, Bible Christianity in Bratton Clovelly was a story of small-scale and individual attention to early adopters who then spread the message, beginning with O’Bryan and Thorne’s visits to the parish in 1818. A Society of seven members was formed, including a young man named John Knight, his parents and his brother. John became a local preacher and in 1830 began 35 years as a Bible Christian minister, the first of six ministers from the parish. John’s brother James, a shoemaker like their father, became one of three signatories to the meeting house certificate for Bratton Clovelly’s first Bible Christian Chapel, built in the village in 1834. William Johns, blacksmith, was the second signatory and provided the land for the chapel, with another blacksmith, William Tremeer, as the third signatory. Another early and influential nonconformist in the village was John Smale, shoemaker, who was converted in 1830 at age 18 and became a local preacher and class leader for the next fifty years. In 1837, John Rice, yeoman of Boasley Farm, was added to the list of Bratton Chapel trustees. These men and their families laid the groundwork for a chapel that would welcome congregations for the next 150 years.

It was unsurprising that John Rice, husband of Alice Hatch, would join the trustees for Bratton Chapel as the denomination was also progressing quickly at the Hatch family’s Boasley Farm in the east of the parish. At the time of his death in 1837, John Hatch, gentleman, had been one of Bratton Clovelly’s principal resident landowners with substantial holdings at Boasley, Blagrove and Broxcombe farms. Upon the death of his wife Margaret a few years later, her will identified their three spinster daughters as executrices for the estate. Along with five married sisters, the Hatch ‘daughters’ would exert a strong local influence on Methodism for decades to come. Immediate attention went to fulfilling their father’s wish that a piece of land at Boasley be consecrated for a Bible Christian chapel. Boasley Chapel was built in 1838, sitting at the eastern edge of the parish and drawing worshippers from Bratton Clovelly as well as neighbouring parishes. The chapel is still active today and remains the site of the only nonconformist cemetery in the parish. In addition to the substantial influence of the Hatch daughters and their yeoman husbands within the parish, their impact stretched farther afield. For example, one of the daughters was personally central to the conversion of Maria Harry of Patchacott Farm in neighbouring Beaworthy, including preaching to a large gathering where ‘tears flowed from almost every eye’. Maria proposed and became one of the first members of a new Bible Christian Society and a chapel was built at Patchacott the year before she died.

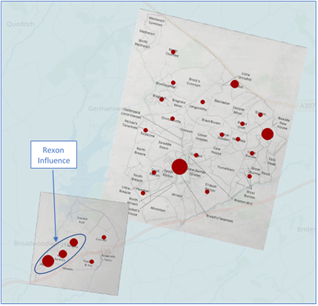

Another early influence on Bible Christianity in the parish came from the growth of the denomination in Broadwoodwidger just west of Bratton Clovelly. John Thorne, brother of Bible Christian leader James Thorne of Shebbear, settled as a tenant farmer in Broadwoodwidger in 1838. He was first signatory to Broadwoodwidger’s earliest Bible Christian Chapel at Grinacombe Moor which opened in 1844. Although he inherited the Thorne family’s Lake Farm in Shebbear, he chose to leave the farm to a brother and emigrate to America with his family to America in 1845. Broadwood Village was only half a mile from Rexon, the southernmost part of Bratton Clovelly parish, and there were many kinship and economic ties between Broadwoodwidger and a number of smallholders at Rexon. Rexon would become the site of the third Bible Christian chapel in the Bratton Clovelly parish, funded by a largely community effort and opening in 1860. It remained active for over 150 years, closing in 2013.

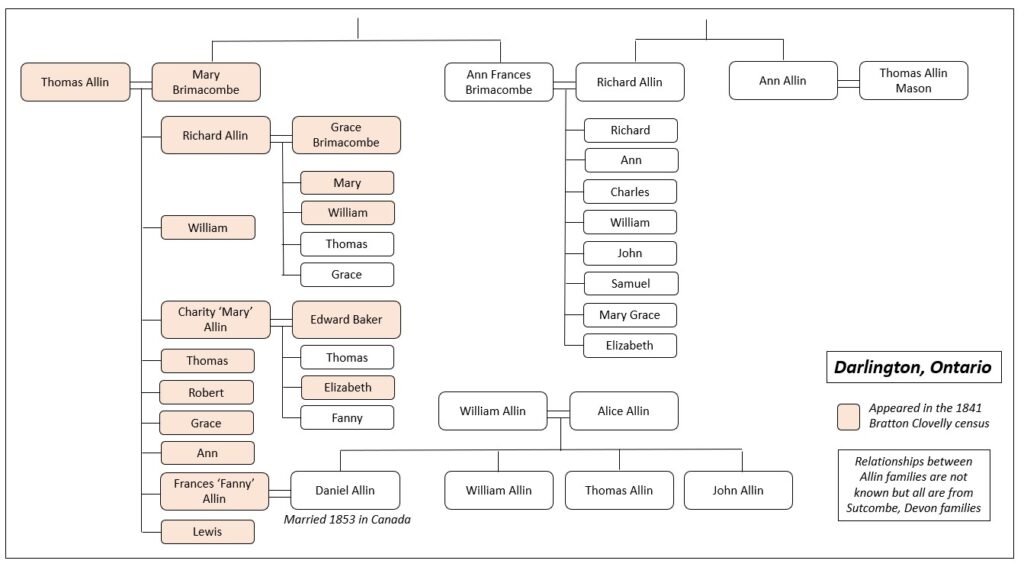

The other area of the parish that had a relatively higher number of nonconformists in the 1841 census was in the moorlands in the north of the parish. Thomas Allin of Sutcombe, Devon became the largest tenant farmer in Bratton Clovelly in 1836, responsible for both Broxcombe and Northcoombe Farms, and was approached by the Okehampton Wesleyan Methodist Circuit to form a Wesleyan Society. The Society never exceeded seven members and only existed to 1842 when Thomas, many of his relatives and the rest of the Society he founded emigrated to Ontario, Canada.

The Growth of Nonconformity

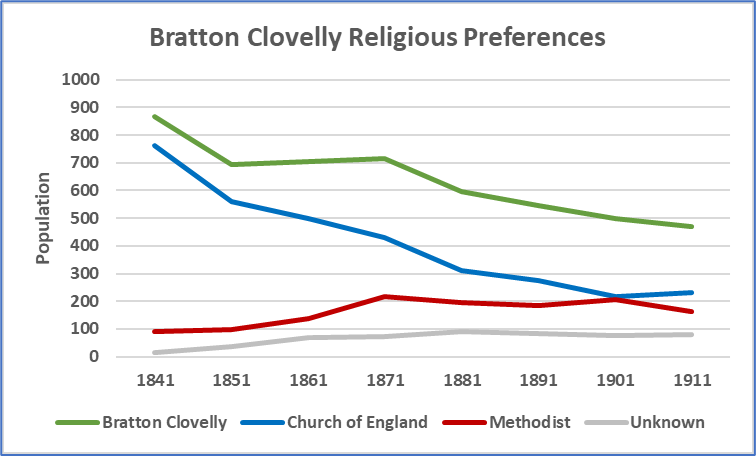

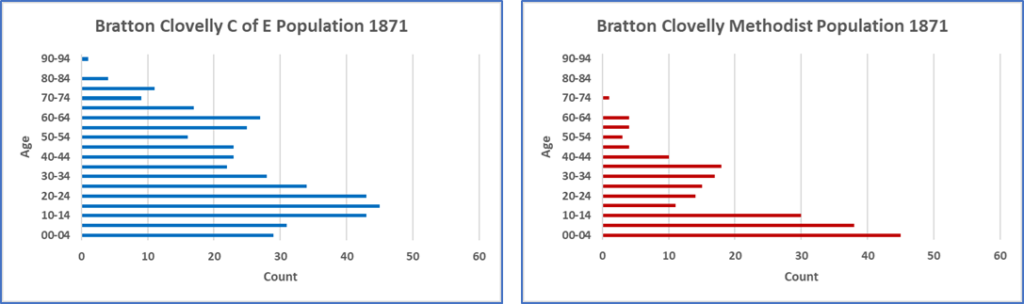

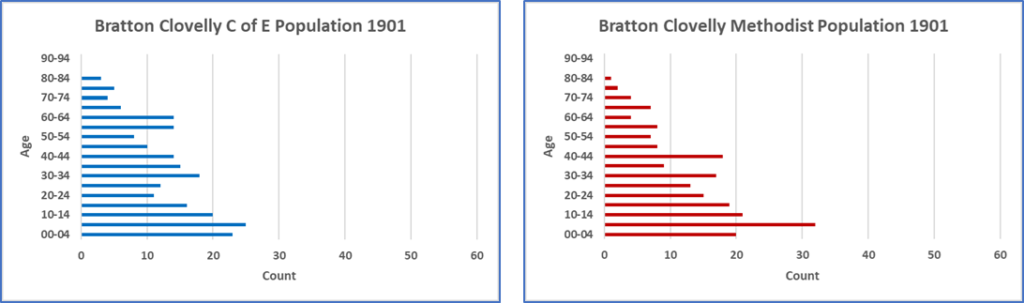

For the half century before 1841, Bratton Clovelly was a place of growth. Like the nation as a whole, higher fertility and lower mortality had fuelled a sustained increase and Bratton Clovelly’s experience was almost precisely that of the national picture rising 50% between 1801 and 1841. Unsurprisingly, the population structure had a broad base, with half of the parish under age 20 by 1841. Unable to develop alternative industries, the growth was unsustainable and de-population began early for the parish. It dropped in size by 20% between 1841 and 1851, with the decline continuing through the end of the century. Although both church and chapel would be impacted by the population change, the growth of the Methodists was rapid and the decline of the Church even more so, with parity reached in 1901. In fact, a substantive decline in actual numbers of nonconformists did not appear until the 1911 census despite the population change.

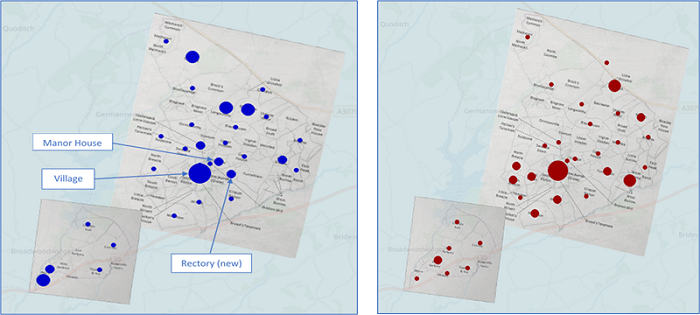

However, although Methodists could be found throughout the parish by 1901, parity was not reached in Bratton Village nor the manor house surrounds. Thomas Ellis Manning and his wife Elizabeth were lord and lady of the manor through the study period and the largest benefactors of St Mary’s Church. In 1892, Mrs Manning contributed thousands of pounds in memory of her deceased sister to an extensive restoration of the church.

The dramatic rise of nonconformity in communities, and the evangelical zeal of denominations such as Bible Christianity, must have been threatening not only to clergymen whose livings were granted to service their whole ‘flock’ but also to the status quo more generally. In North Devon as well as Bible Christian missions farther afield, newspapers and denominational literature reported scenes of verbal and physical abuse, arrests and evictions of the new arrivals. However, the evidence is of more subdued reactions in Bratton Clovelly, perhaps related to the prevalence of farmers and tradesmen amongst the early adopters of Methodism. Minister Samuel Crocker reminisced of his time in Bratton Clovelly in the early 1850s that the Bratton clergyman, Rev Edward Budge:

“was so opposed to the work that he had bills put up to caution people and keep them from attending meetings. He said the revival was ‘perversion not conversion’, and that no one would know his sins were forgiven until the Judgment Day.”

Tensions surfaced again in the 1880s when William James Harris, JP of Halwill, churchman and invited speaker, stated to a large and distinguished audience at the opening of a new Bible Christian Sunday School in Bratton Village that ‘he noticed a liberal donation from a resident clergyman in the neighbourhood – (hear, hear)’. Rev Edward Seymour’s public response was swift:

“I trust you will publish my disclaimer I never did anything of the kind, and I consider the statement as injurious to my character for consistency and loyalty to the Church. I cannot assist, even indirectly, what I consider wrong and mischievous.”

Despite the apparent stability of Methodism amongst the parish residents, baptisms across the Northlew Circuit including Bratton Clovelly indicate that the growth of the Bible Christian denomination may have peaked in the circuit in or near the 1870s. This peak is consistent with the slowing of the denomination’s national annual growth rate in this timeframe, a denomination where the majority of members were always from Devon and Cornwall. However, Bratton Clovelly’s nonconformist population continued to grow until at least the end of the century, unlike the national membership of Methodist denominations as a percentage of population which had begun to stagnate and even decline.

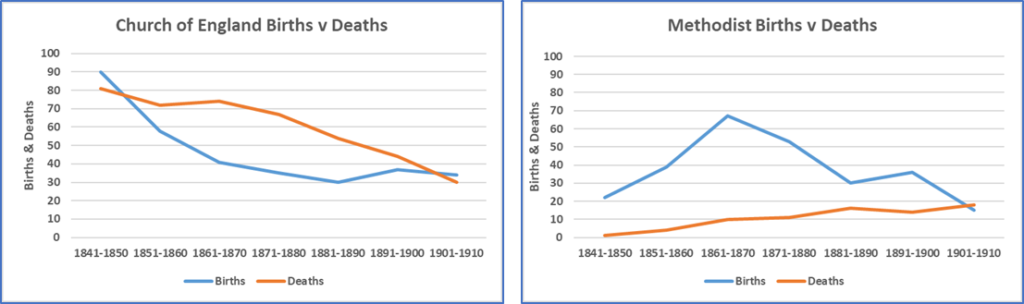

The continuing rise in Bratton Clovelly can be explained at least in part by the age dynamics of the parish’s nonconformists. While denominational literature focused on the continuing impact of removals to parts of the country where Bible Christianity did not have a presence, and the high number of members emigrating overseas, the relative youthfulness of Bratton Clovelly’s nonconformists provided a large base of children to carry their upbringing into adulthood and outweigh the impact of departing adherents.

By the time parity between conformists and nonconformists was reached at the end of the century, the Methodist population had aged and the age differences between denominations were much diminished albeit in a smaller parish. By 1911, Bratton Clovelly’s Church of England population would become more youthful than the Methodists. The findings are consistent with Currie’s observation regarding Methodist denominations more generally that ‘The faithful members’ characteristics are most clearly shown by the fact that, after 1910, they were steadily ageing’.

Occupational Analysis

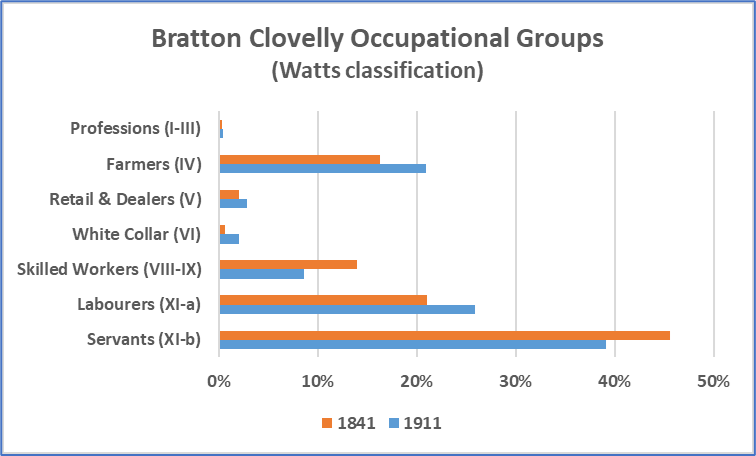

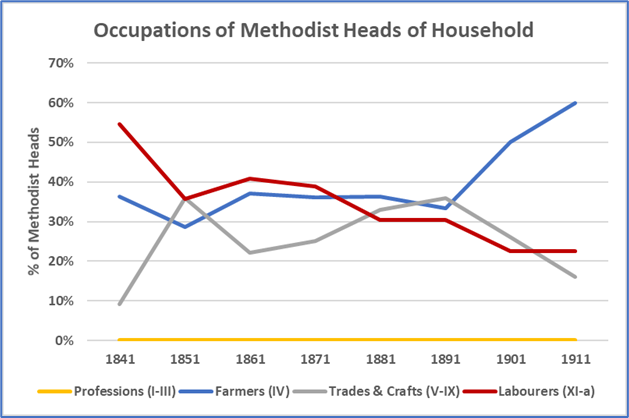

To better understand the composition of the respective religious communities in the parish, a simplified version of Watts’ elevenfold occupational classifications was applied. Watts’ classification scheme was chosen because his descriptions identified virtually all occupations found in the Bratton Clovelly censuses, it clearly delineated the main classes of workers found in the parish and there was some economic basis to the classifications even though representative wages were from the 1830s. The scheme was first applied to all residents of the parish with an occupation in order to provide a profile for the parish as a whole in the 1861 and 1901 censuses. Throughout the study period, the parish was one of farmers, craftsmen (skilled workers) and labourers, with a large base of young workers employed as servants prior to marriage. In terms of overall composition, it was the young servants who absorbed most of the impact of the sharp decrease in population and enabled the adult workforce to remain relatively stable.

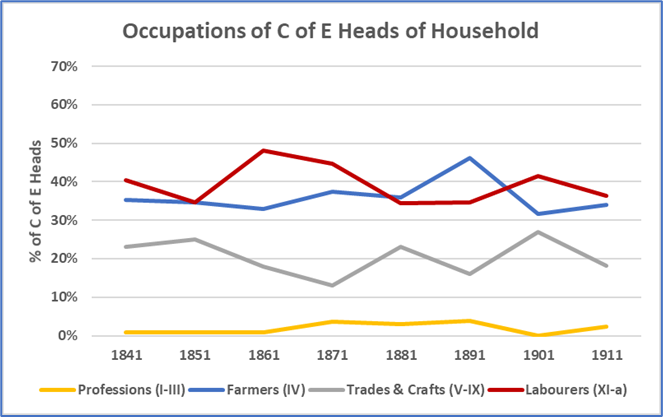

Watts’ scheme was not designed for use in representing the total workforce. Rather, he used it to classify fathers’ occupations in baptism registers so neither the large number of young servants nor female workers feature in his county-level breakdowns. For comparability, subsequent analyses in this study are restricted to heads of household. Overall, the religious preferences of heads of household are reflective of the religious preferences of the parish’s total population, with the conformist population declining more rapidly than the general decline and the nonconformist population continuing to increase throughout the 19th century.

Given the small sample sizes when decomposing to occupational groups, the classes of retailers and white collar workers were combined with skilled workers. Overall, the percentage of heads of household who were farmers increased from 1851 to the end of the study period. Essentially, while the parish reduced in population, the actual number of farmers stayed fairly constant. Clearly, the availability of farms was the primary determinant of the number of farmers needed. On the other hand, the number of labourers declined from 1861 possibly due to increasing mechanization which arrived relatively late to the rugged West Devon countryside.

Although there is increased volatility likely due to sample size, the relative occupational composition of the Church of England heads of household remained mostly representative of the parish as a whole for much of the study period. However, in the latter decades the percentage of Church of England farmers did not keep pace with the increasing total percentage of farmers in the parish.

For the nonconformist heads of household, the divergence from parish-wide trends in the latter decades was dramatic. While the percentage of Methodist heads of household working as labourers declined throughout the study period, the percentage of farmers increased sharply between 1891 and 1911 resulting in a denomination where 60% of household heads were farmers compared to the parish-wide percentage of 44%. By this time, the proportion of labourers had dropped to 23% compared to a parish-wide percentage of 32%.

Social Status and Community Influence

Watts recognised that occupations identified in registers and censuses are only a rough approximation to social structure and influence and noted for example that the farmer class ‘covers a whole spectrum of wealth and social standing’. To identify potential relationships between religious preference and community influence, the parish’s gentry and farmers were further examined.

Occupations in censuses appear inadequate for identifying those in Bratton Clovelly in the gentry class, rarely highlighting anyone except the vicar in each census. To better distinguish the highest status individuals in the community, trade directories were used to identify clergy, manor lords and ladies, those listed as principal landowners who were resident in the parish and those categorised as or grouped with ‘clergy & gentry’. Thirty-two individuals, including spouses, were identified with six to ten resident in the parish in each census. Some of the gentry, especially later in the study period, were new arrivals of gentlemen farmers, older wealthy widows and relations such as sisters of gentry families already settled in the parish. Many in the group were born outside of Devon and Cornwall and over 90% were Church of England adherents, consistent with studies identifying that the gentry had only a scant presence in evangelical nonconformist congregations. They exerted considerable influence on the community, for example with the vicar’s leadership of the National School from 1837 to the opening of the Board School in the 1870s. In addition, Thomas Ellis Manning and subsequently his widow Elizabeth owned many farms and much of Bratton Village until the fragmentation and sale of manor properties in 1919 gave the opportunity for parishioners to purchase homes that had been in their families’ tenancy for generations.

Only three gentry nonconformists were identified in Bratton Clovelly, all related to John Hatch, gentleman, who had passed away just shortly before the study period and the opening of Boasley Chapel on his farm. Daughter Peggy Hatch was a spinster and executrice for the estate left by her parents, William Hatch Martin was the son of John and Mary (Hatch) Martin and grandson of John Hatch, and Fanny Glass was the wife of William. Peggy remained in the parish until her death in the 1880s and William continued farming in the parish until the 1890s.

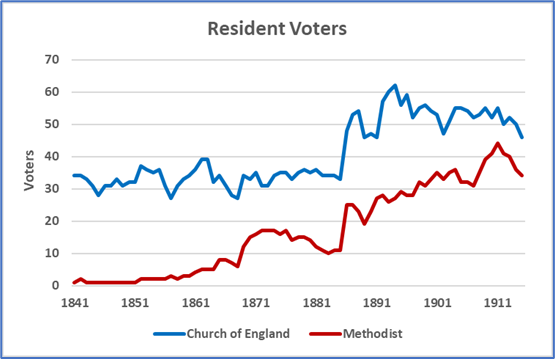

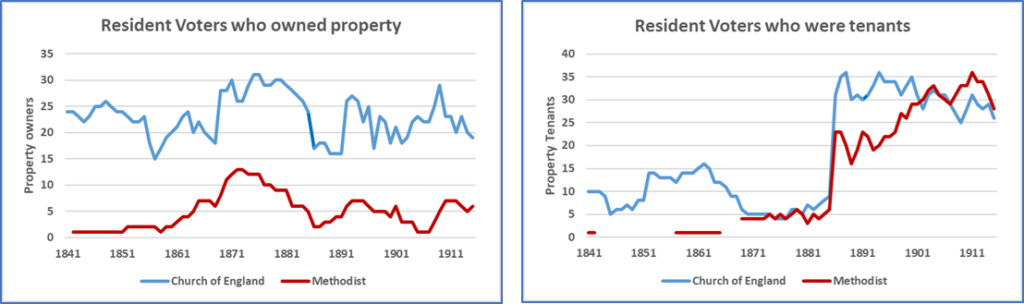

For further examination of those with the occupation of farmer, resident voters in the Bratton Clovelly voter rolls were linked to the study population. The increasing number of nonconformist voters, like the increasing number of nonconformist heads of household, indicates rapidly increasing influence. However this source did have limitations including major changes as tax legislation evolves, inconsistencies in the descriptions of elector type, and cases where an elderly father might continue to be listed in the rolls until death even though responsibility for the family farm had transitioned to the next generation long prior. Despite the limitations, to a great extent the rolls did distinguish farm owners from tenant farmers as a means of better understanding social status, and the rolls may have helped to distinguish larger farm holders from smallholders particularly earlier in the study period.

Although the increases partially reflect the changing profile of religious preferences in the parish, the Second Reform Act of 1867 significantly increased nonconformist representation in the parish voter rolls and the Third Reform Act of 1884 had a major impact on men in both church and chapel.

Despite the quickly expanding electorate, the rolls identify that the Church of England voters were much more likely to be property owners than the nonconformist voters throughout the study period. It can also be seen that those who became eligible for voting through the Reform Acts were primarily tenants, both conformist and nonconformist. While eligibility to vote may have increased status and opened new opportunities for community roles and influence, the highest status individuals in the community emphatically remained Church of England adherents. In addition, a number of principal landowners continued to live outside of the parish throughout the study period.

The survival of the first two decades of minutes from Bratton Clovelly’s Board School, 1874-1894, provides a snapshot of influencing in the community, education being a national focus for both church and chapel. When the parish’s School Board was formed, the vicar had always been responsible for the original National School in the parish and continued as Chairman of the elected School Board. The other Board members were two substantial Church of England farmers, Edward Rice who was Methodist and a grandson of John Hatch, and another substantial Methodist farmer. In 1877, William Hatch Martin replaced Edward Rice when Edward left the parish. In fact, for the next decade every time a churchperson left the Board, they were replaced by another churchperson and the same was true for the Methodists. Throughout this period, voting was along religious lines for essentially every significant motion raised. Repeatedly, one of the churchpeople would raise and second a motion and then one of the chapel people would raise an amendment or vice versa. In virtually all cases, the majority churchpeople prevailed, on topics such as the process for appointing the schoolmaster, naming the vicar’s family as managers of the school and whether or not the Board meetings should be open to reporters and ratepayers.

In 1886, for unspecified reasons Rev Seymour‘s family resigned as managers of the school and he resigned from the School Board. William Dawe became Chairman, the Methodist son of a Cornish copper miner who had worked his way up from agricultural labourer to grocer, carpenter and then owner of a 120-acre farm. The School Board majority changed to the Methodists for the first time, a majority that would not be reversed. Several decades later in 1908, the newspapers reported that the vicar Gregory Bateman was deposed as parish representative on the Bratton Clovelly School Board because he had appointed Miss Dora Whitmore, gentry churchwoman, to the Board without consultation. The article identified that by then the School board was composed of five Methodists and one Church of England member. The churchpeople raised major issue with Rev Bateman being deposed, with gentleman farmer Percy Kenyon-Slaney declaring, ‘One member to five was not fair play, and Englishmen like fair play’. The Parish Council did not change its decision.

Births, Deaths and Migration

Population change had a significant impact on the rate at which Methodism grew and the Church of England declined in Bratton Clovelly, including change due to births, deaths and migration. The youthfulness of the nonconformists previously discussed impacted not only the nonconformist birth rate but the death rate as well. From 1841 to 1901, births substantially outpaced deaths amongst Methodist adherents, while the opposite occurred from 1851 to 1901 amongst Church of England adherents.

In this study, migration is defined as any change of normal residence beyond the boundaries of the Bratton Clovelly parish but within the British Isles. In-migration refers to moves into and out-migration to moves out of the parish, while emigration refers to moves overseas. In a period where the total population reduced by almost 50% and high levels of local migration were the norm, the net of in- and out-migration could be expected to be negative overall for both conformist and nonconformist populations. This type of migration was primarily driven by the ongoing movement of tenant farmers, agricultural labourers and servants over short distances.

Bratton Clovelly In-migration less Out-Migration as Percent of Adherents

to Church of England and to Methodism, 1841-1911

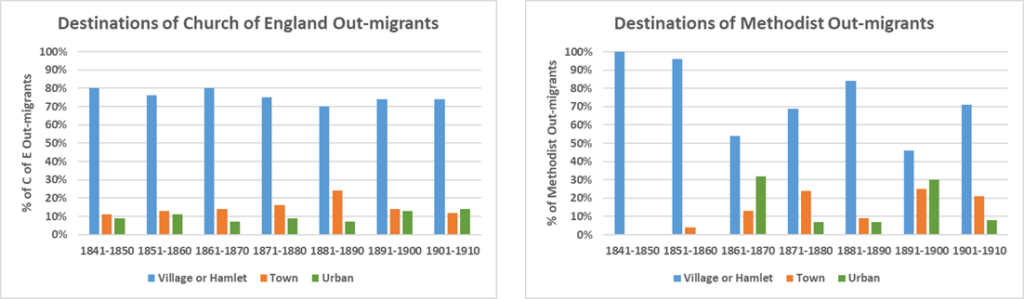

However there were several distinguishing characteristics in the migration patterns of church and chapel adherents. First, in-migration was considerably more localised for Methodists than for Church of England adherents. Further investigation is needed but contributing factors may include the strength of Methodism in the local area as well as higher status in-migrants, predominantly Church of England, who often migrated from outside the local area.

A second and perhaps more surprising difference was that, in all but one period after the 1861 census, Methodist out-migrants chose to move to towns and urban areas more frequently than Church of England adherents. The nonconformist out-migrants were often families or related groups, with over 40% dependent wives and children. Two-thirds of the movement to urban areas was to the fast-expanding Plymouth area with another 25% to London. Moves generally related to work, with the most prevalent occupations being general and higher skilled servants, both female and male, followed by tradesmen and craftsmen. These moves may have been prompted by the diminishing opportunities for servants and craftsmen in Bratton Clovelly as the parish continued to lose population. In addition, there were significant groups of those with occupations that required movement such as nonconformist ministers, military members, constables and railway workers. A particularly close-knit group migrated between 1891 and 1901, when William Lovill, William Spry and Sydney Smallacombe departed to become constables in Devonport in the Plymouth area. They were joined by William Lovill’s sister Mary who married William Spry as well as two of William Spry’s sisters who married other constables in Devonport.

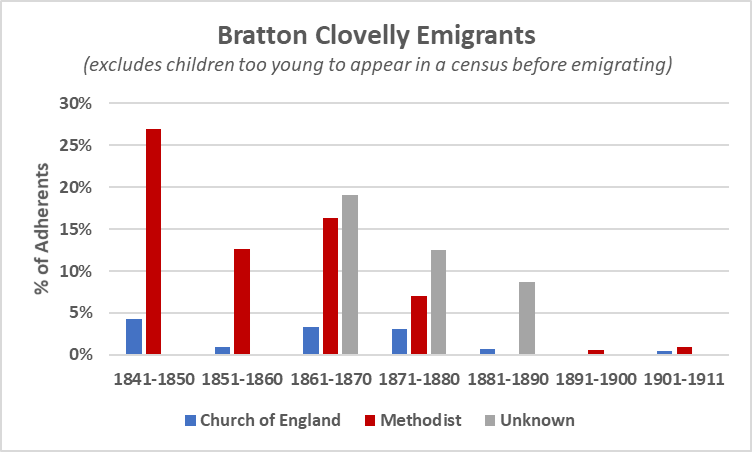

Turning to overseas moves, nonconformist patterns of emigration contrasted sharply with those of Church of England emigrants. Between 1841 and 1850, over one-quarter of parishioners identified as Methodist in the study emigrated overseas. Large percentages of nonconformists continued to emigrate for the next four decades, a period when total emigration accounted for about 60% of the total population loss from the parish as it decreased in size by almost one-third. Considering the Methodists’ propensity to both overseas emigration and internal migration to towns and urban areas, the question is raised but left open as to the extent that the denomination’s ethic of self-improvement may have been a motivator of these riskier choices.

Bratton Clovelly’s nonconformist emigrants had a strong preference for Canada as their destination and many travelled in kinship groups, similar to Few’s findings on emigrants from North Devon parishes. Most settled in Ontario province where newly opened lands were widely available. Trade routes with Canada had long operated from North Devon ports for the fishing industry and subsequently the timber shipments that became prominent during the Napoleonic Wars, and 90% of emigrants sailing from Bideford between 1840 and 1856 were destined for Canada. Methodist communities quickly grew and, in 1831, the Bible Christians began sending ministers to North America. The information flow between Devon and North America was strong, denominational magazines carrying reports of the overseas mission work and friends and family who had already emigrated sharing news of their experiences. Unsurprisingly, a significant number of Bratton Clovelly’s Church of England emigrants also chose Canada and half of the parish’s emigrants who went to the United States chose Ohio or Wisconsin, the two places where the Bible Christians established missions in the States.

Although the parish’s emigrants each had their own reasons for their decision, they were almost all families of farmers and agricultural workers. One of the earliest and biggest emigrant groups was that of Thomas Allin, his wife Mary Brimacombe and kin from multiple parishes who left in 1842 for Canada West, later to become Ontario. Thomas was a large tenant farmer of Northcoombe and Broxcombe farms and founder of the Wesleyan Methodist Society in Bratton Clovelly. Shortly before emigrating, he had finished a difficult court case with his new landowner who Thomas claimed was sabotaging his improvement work so that the property could be let in lots. Other families who had baptised children in his Wesleyan Methodist Society also emigrated to Ontario at that time.

Emigration from Bratton Clovelly to the South Pacific took place slightly later but the emigrants had much in common with those who had chosen Canada. James Rundle, Bible Christian and tenant farmer of Higher Voaden Farm, was an assisted passenger to Yankakilla, South Australia in 1863 with his wife Jane Ellis and five children. Their story is told in a 2013 publication written by some of their many descendants. Two brothers of James had previously emigrated to Canada but James and Jane instead joined Jane’s sister Mary and her husband Richard Westlake who had left for Australia in 1855. By the time James and Jane settled in Bald Hills, there were already Bible Christian and Wesleyan chapels in the township.

Over time, the nonconformists increasingly chose locations within England and Wales, including towns and urban areas, and emigration slowed to a trickle. The last of the nonconformist emigrant groups during the study period left for New Zealand in 1880, comprising Wrixill Farm owner and Bible Christian Samuel Trewin, his wife Mary Ann Stapleton and at least four children. The last emigrant found in the study was 20-year-old John Hall Lovill, religious preference unknown, who lost his life in 1912 when he chose to travel to the United States aboard RMS Titanic.

Summary

The rural parish of Bratton Clovelly lends itself well to an analysis of dissent in the community at the level of individuals. The sparse population, relatively simple occupational structure and small number of religious denominations limit the complexity of the analysis. The parish did have much variation in population during the study period, but the internal movement was localised and the overseas movement was primarily to destinations where major record sources are accessible. On the other hand, those factors that make the parish well-suited for such analysis also limit the applicability of the findings. The study results are based on small sample sizes and can only speak to the local experience of dissent. In addition, the significant portion of parishioners where religious preference could not be determined means that the results are best viewed as indicators only for further research.

Accepting these qualifications, the study population does provide evidence of both the development of dissent in Bratton Clovelly and distinguishing characteristics between the Methodist and Church of England adherents in the community. The early development of Wesleyanism in nearby Cornwall along with the establishment of Bible Christianity in Shebbear only ten miles from Bratton Clovelly ensured that dissent would reach a community that had long been fully in the care of a stable and active Established Church. The Methodists were successful in bringing a compelling message and despite rapid de-population, nonconformity continued to grow throughout the latter half of the 19th century while the Church of England steadily declined. Even after the denomination itself reached its peak growth rate, actual numbers of adherents and influence in the parish continued to grow.

Historically, Bratton Clovelly was a parish of many property owners and scattered sizeable farmsteads, populated by farmers and their workers unlikely to be beholden to a central authority. The Methodist message was carried to individuals in the village and on the farms, a message that resonated with early influential adopters able to establish chapels and spread the word in a relatively receptive environment. The tireless Bible Christian ministers and preachers attracted farmers, craftsmen and labourers but, in Bratton Clovelly, it was ultimately the farmers who would become the most prevalent group in the denomination. These farmers were for the most part neither gentry nor property owners however they increasingly exerted influence throughout the community.

Through much of the study period, a particular challenge of the Methodists was the substantial leakage of adherents to emigration and internal migration to areas where the small Bible Christian denomination did not have a presence. Yet the Methodists in the parish were on the whole a young group with high birth rates and low death rates that compensated for the migration losses. The Methodist migrants were willing to travel longer distances and to less familiar destinations than the Church of England migrants, supported by the availability of transport and information flows with chapels and like-minded groups ready to welcome them into distant communities.