The following write-up is an abridged version of a study done for the Advanced Diploma in Local History, Oxford University Continuing Education. The unabridged version, with full references, can be viewed at Bratton Clovelly Migration 1841-1861.

Bratton Clovelly Migration, 1841 to 1861

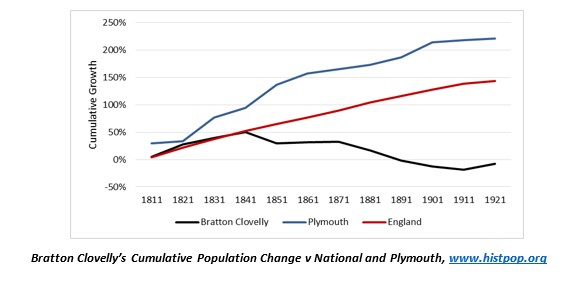

Bratton Clovelly became an early victim of Victorian rural depopulation, losing one-fifth of its population between 1841 and 1851, the beginning of a decline that continued through the century. For the half century before 1841, Bratton Clovelly had been a place of growth. Like the nation as a whole, higher fertility and lower mortality had fuelled a sustained increase and Bratton Clovelly’s experience was almost precisely that of the national picture rising 50% between 1801 and 1841. Unsurprisingly, the population structure had a broad base, with half of the parish under age 20 by 1841.

However, almost 80% of the parish’s workforce was employed in agriculture and the land imposed constraints. The fast-approaching decline of Bratton Clovelly, like other rural parishes unable to develop alternative industries, may have mostly been a response to having too many mouths to feed.

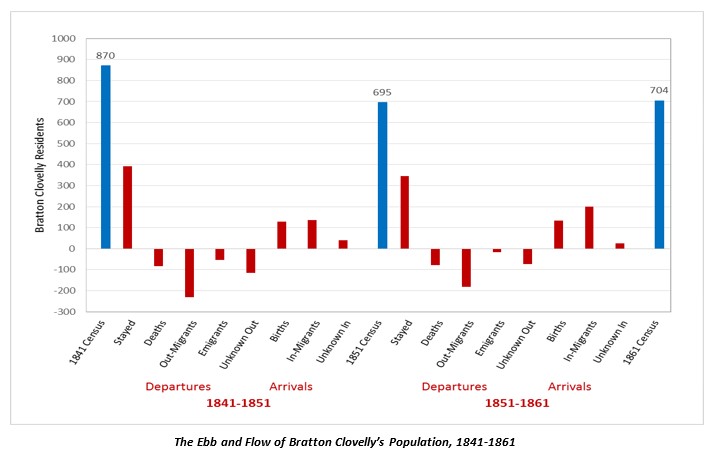

Each component of population — Births and Deaths, Internal Migration and Overseas Emigration — was investigated for the period 1841-1861. The study will be extended to other years in future.

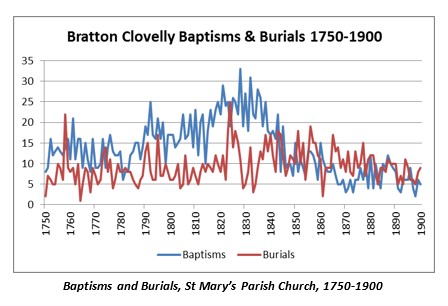

Births and Deaths

Throughout its modern history, Bratton Clovelly had been a long-lived place. Low mortality prevailed in the timeframe of our study, with an average age at death of about 47 and a median age of about 55, the national average being about 40. In addition, the average marital age fell by two years to 26 for men and 24 for women between 1821 and 1861, reflecting national trends. Another potential factor in birth rates, those who did not marry, showed no significant change at about 5% for men and women over age 29.

These indicators point to a rate of natural increase at least stable and probably continuing to increase during the study period. In addition, there were more births than deaths in the parish. So, population in Bratton Clovelly was inversely related to natural increase during the period 1841-1861 and the population change must have been due to migration or emigration in excess of the 20% decline seen in the population figures.

Migration within the British Isles (Internal Migration)

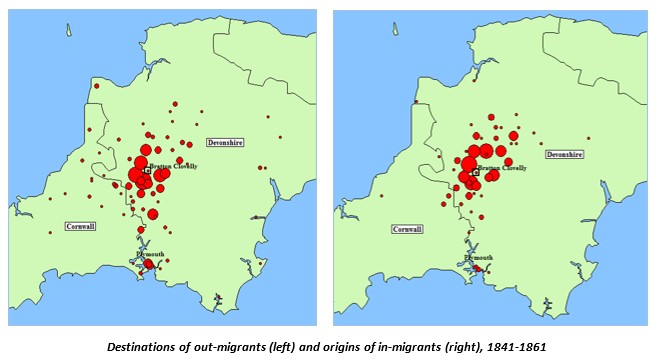

Internal migration was a normal part of life for Bratton Clovelly residents. In 1841, only about 55% had been born in the parish and by 1861, almost half of these native-born had moved elsewhere. However, they may not have thought of themselves as migrants, since 98% of the internal moves identified to date were within Devon or neighbouring Cornwall parishes, with only a handful of people arriving from or departing to anywhere else in England during the study period.

Between 1841 and 1851, the parish’s population declined by 20% whereas it remained essentially stable from 1851 to 1861. Yet, there were 365 migrants in the period of decline and 382 in the stable period, about half of the total population in each period. Movement was continuous, but population change only occurred when in-migrants and out-migrants were out of balance. This happened between 1841 and 1851 when, of those whose origins and destinations can be determined, 77 more people left Bratton Clovelly for local destinations than came into the parish – accounting for 44% of the total decline.

The migrants were more likely to be unmarried and younger than the population who stayed in the parish, with most difference in the 10-29 age range. In addition, out-migrants were more likely to have been born outside of the parish than those who stayed, 44% versus 36%, and most moved for work or marriage. Of longer-term import, a net of 8% of the migrants moved to towns and urban areas, mostly Tavistock and Plymouth. Occupational choices featured local mining and quarrying which would only last into the next decade, the Plymouth Dockyards and domestic service.

Occupational View

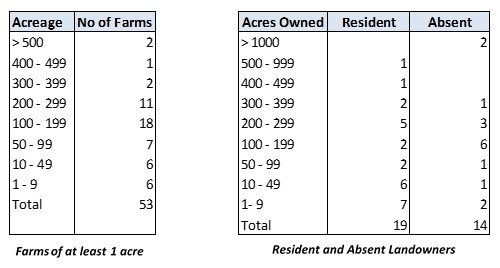

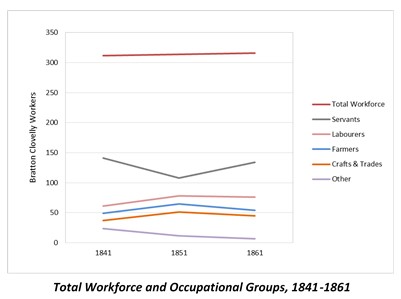

Bratton Clovelly in the study timeframe – its history, culture, social structure and economy – was about land. Almost 80% of its workforce was employed in agriculture, including farmers, farm labourers and farm servants. The land was clay, best for cattle and sheep, with about half arable mostly for wheat and oats. Markets were local, the railway still decades away and roads sometimes impassable in the wet weather. Mechanisation would have been difficult in the challenging terrain. The farms were on average 155 acres each, some good and some poor. Although there was movement amongst farms, the owner occupiers were still attentive in their wills to keeping properties intact whilst managing to provide for all of their children through arrangements such as tenancies-in-common. However, eleven farms were advertised for sale in the study period, another four for long-term lease, so opportunities were available. Although homes and wages were modest, both the farmers and farm labourers were at the heart of the local economy and neither contributed to the parish’s decline. In fact, both groups showed a net increase through the study period.

It was somewhat different for the small number of craftsmen and tradesmen of the parish but to the same effect. Almost 20% chose towns and urban areas as the parish shrank. However, their migration rate was not high and these occupations often seemed transitional, with agricultural labourers becoming craftsmen and craftsmen becoming farmers or agricultural labourers. In the end, there were more craftsmen at the end of the study period than at the beginning but one of the two inns had not survived.

Overall, the surprising impact of the population decline on the workforce as a whole was that there was no change. The young servants, about 45% of total workers, absorbed the change with work continuing as usual for the adults. Servants dominate the overall statistics for internal migration. Where opportunities existed, they could take servant work in the parish or join the adult workforce. Where opportunities did not exist, they moved on, to new locations and perhaps new types of work. The change in the servant workforce was sharp between 1841 and 1851, but after the more stable decade following, even the servant workforce was little different in absolute terms. As a smaller parish, there was a higher percentage of workers, 45% in 1861 versus 36% in 1841. There were fewer male servants, female domestic servants had replaced female farm servants, and female workers had increased from 18% to 25% of the total workforce. Otherwise, substantive change is not apparent.

Lifecycle View

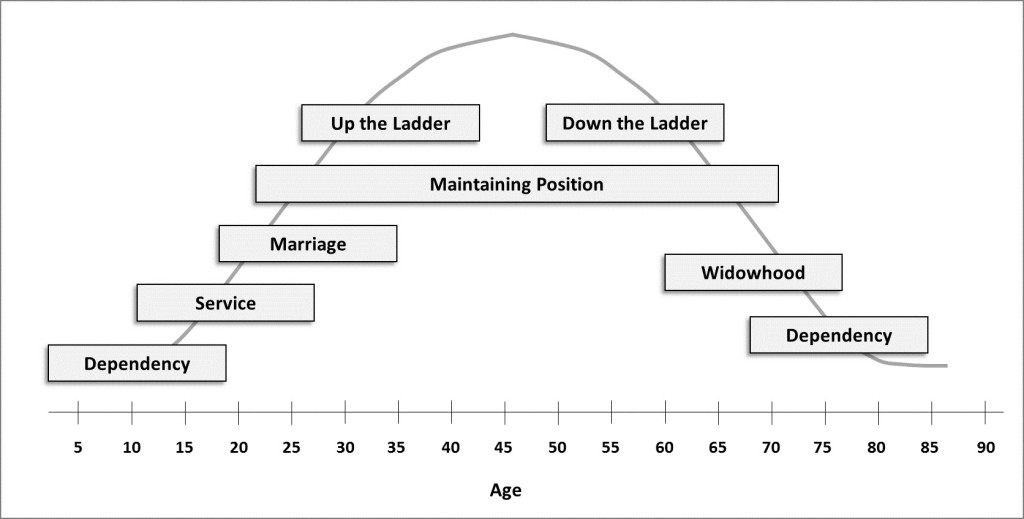

Accepting that individual migration decisions may have been complex, there are unifying themes at various points in the migrants’ lifecycles when considered collectively. Realistically, the age boundaries when each broad motive dominates may vary considerably between individuals but a simple model can reflect much of the experience.

Dependent children under 20 moving with their parents comprised a substantial proportion of migrants throughout the study period, 25% of those moving into the parish and 15% of those moving out. As 28% of the total parish were dependent children, they may have been a constraining factor in local out-migration. However, given the large families that moved overseas in the 1841-1851 period, a much higher proportion of 38% is found amongst this group. Dependent children may have actually been a motivator for the early emigrants.

Those working as servants account for the largest amount of movement in the parish, with 28% of total migrants (less excluded individuals) either coming to the parish to work as a servant or leaving for a servant role at their destination. Most were male farm servants aged between 10 and 24, with the children of agricultural labourers entering service on average earlier and in higher proportions than those of farmers and craftsmen. During the study period, the age of female workers joining the workforce increased, age 15-19 becoming the norm, simultaneously with an almost complete transition from agricultural to domestic service.

Marriage was the next key transition, with at least 15% of migrants moving within the decade of marriage. For men, the figure mainly includes moves from farm servant to agricultural labourer necessitated by marriage rather than moves with a more substantial change in job type. For women, the moves reflect establishing co-residence, for which brides moved about twice as often as grooms. Subsequent to the decade of marriage, the dependent moves of wives accounted for about 10% of overall moves.

For adult workers, many work-related moves were between the same types of jobs at origin and destination, such as agricultural labourers moving between farms or craftsmen between villages. This type of move accounts for just over 10% of all moves, while those moving to more favourable positions account for another 10%. More favourable positions are exemplified by moves to larger farms or better wages, craftsmen moving from journeyman to master, agricultural labourers or craftsmen becoming farmers, house servants becoming lady’s maids, and tenant farmer emigrants becoming land owners overseas. This figure is probably understated though since neither the quality of the farms, nor the size of farms where migrants came from or went to, has been considered. A few moves to less favourable positions were also detected, for example where a farmer downsized or became an agricultural labourer in later life.

A small group of moves was due to changes in family circumstance, most associated with widowhood. A few moves were also related to pauperism, although this category needs further investigation since a preliminary review of surviving out-relief rolls indicates that the census records may not reflect paupers still working.

In hindsight, all of the components of the basic model proposed for migration have socioeconomic aspects albeit alongside non-economic drivers.

Emigration

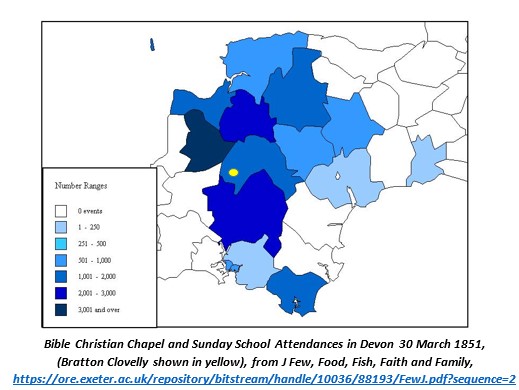

Through the study period, 70 Bratton Clovelly residents from the 1841 and 1851 censuses chose to move overseas, accounting for 40% of the parish’s population decline. The emigrants included an almost equal number of males and females, a slightly higher female to male ratio than the general Bratton Clovelly population. Their occupational distribution reflected the home population, and most of the farmers had been tenant farmers in England. However, the emigrants differed from the home population in significant ways. They included a disproportionately high number of 20-29 year olds and married couples, reflecting the many young families who emigrated. Also, 60% of the emigrants were not native to Bratton Clovelly, reflecting a relatively mobile group. Although religion is only known for those who settled in Canada, it seems likely that there was a particularly high number of Bible Christians among the emigrants, an offshoot of Wesleyan Methodism based in nearby Shebbear, Devon with two chapels already in Bratton Clovelly. Even where religion is not known, the emigrants overwhelmingly chose Ontario as their destination, the overseas heartland of Bible Christian mission work, and most settlers in the USA chose Ohio or Wisconsin, the two places where the Bible Christian Canadian Conference had their most active missions in the States. Australia would not become a major destination until the 1860s.

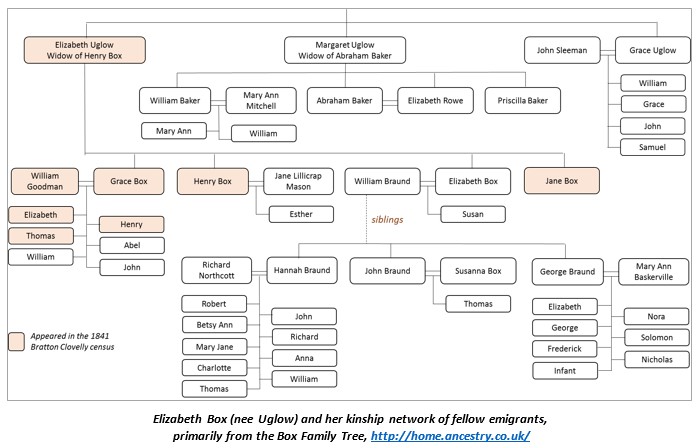

Statistics are interesting but the emigrants’ individual stories aid in considering motives. In 1839, Henry Box died leaving £300 in effects to his wife and two sons, along with the remainder of what was probably a 14-year tenancy on the 228-acre East Banbury farm. He also set aside £40 to each of his three daughters. He and his wife Elizabeth were recent in-migrants to the parish likely from Cornwall, and Henry only briefly appeared in the 1837 Voters’ List for the parish before his death. East Banbury was a desirable farm, about half arable and half pasture, attracting an assessment of £10 in the 1845 Tithes and owned by the largest landowner in the parish. Following Henry’s decease, Elizabeth took charge of the farm, appearing as a farmer and head of an 11-member household in the 1841 census including her children, son-in-law, grandchildren and farm servants. In 1849, Elizabeth along with over fifty kin, left England to settle in Racine, Wisconsin, USA. She and her relatives who had been residing in Bratton Clovelly in 1841 accounted for over 10% of the parish’s emigrants during the study period.

Why Elizabeth’s family left and why they chose Racine can only be surmised. Her farm tenure was probably nearing an end but many tenant farmers were long-term and renewal was probably possible. Labour may have been in short supply due to high levels of emigration in the region, but Elizabeth’s large kin network probably buffered her from such shortages. However, she and her children had money to buy land, which they did soon after arrival, like 75% of Bratton Clovelly emigrants. The States were the most popular destination for English emigrants at the time but no one else from Bratton Clovelly had chosen Wisconsin. Although indications are that Elizabeth and her immediate family were Church of England members, she would have undoubtedly known of the Bible Christian missionary work in Wisconsin. Newspapers also disseminated emigrant stories and correspondence along with adverts for passage.

Whatever the reasons, the decision to emigrate was a major one. The passage was about six weeks and dangerous, with two of Elizabeth’s youngest kin dying at sea. The Wisconsin Territory had only been opened to settlers little more than a decade prior following the Black Hawk War, and statehood was only granted the year before her arrival.

The experience of Elizabeth and her family was not entirely unique. Thomas Allin, his wife Mary Brimacombe and a large kin group emigrated in 1842 to Canada West, later to become Ontario. Thomas was a tenant farmer of Northcoombe and Broxcombe farms, the largest in Bratton Clovelly but home to the moorlands and its vestiges of ancient common rights in the northern part of the parish. He had just finished a difficult court case with his new landowner who Thomas claimed was sabotaging his improvement work so that the property could be let in lots. Thomas and his relatives, a Wesleyan Methodist family, included over 20% of Bratton Clovelly’s emigrants in the study period. In addition, it appears likely that all of the families in the small Wesleyan Methodist Society he had founded in about 1837 also emigrated at this time. Most of the remaining emigrants from the parish also travelled in family groups, recognising that the low number of those who travelled alone could be significantly understated due to the difficulty of locating them in the many possible destinations. Few identifies a similar pattern of movement in her case study examination of several North Devon parishes including Bucks Mills, a parish dominated by the surname Braund like Elizabeth Box’s in-laws, where ‘emigration was almost all conducted as extended family groups and prompted by affiliation to the Bible Christian Church.’

Summary

Bratton Clovelly’s population declined by 20% between 1841 and 1851 because more people moved out of the parish than moved into it. Most of the net decline can be attributed to short-distance internal migration and another 40% to emigration. The main reason so many people left the parish was probably as a response to the 50% increase in population between 1801 and 1841. The farms continued intact and were able to sustain the labour force, but the land and transport systems constrained the parish’s ability to respond to a large population increase. Simultaneously, foreign shores made more familiar through early Methodist emigrants and missions provided the chance for land ownership and an independent future for families and kin in like-minded communities, while Devon towns and cities attracted others through better wages and varied employment options.

The young people of the parish absorbed the change, through the institution of service and the law of supply and demand. The balance of servant in- and out-migrants could flex in response to economic conditions, keeping the adult workforce remarkably stable and placing the youth in the types of jobs and locations where labour was needed. They did not have to travel far to achieve the structural change needed by the parish, quickly reducing the parish’s over-sized base of children. It was a mechanism for maintaining equilibrium in the face of change.